Um, actually... that's not a good heuristic for how well a list is sorted

Recently I’ve been watching a lot of Um, Actually, a show on dropout.tv that pits comedians and nerd celebreties against one another in a trivia gameshow format. The show is really good, but occasionally, they do something that really irks me: a common format for the trivia question will have the contestents attempt to put a list in order. For example, “sort these books by release date” or “order these movies by box office revenue”. The prompts are fun, but the way that the results are scored is infuritating: They count all of the items that are in the right slot when compared to the correctly sorted list. higher scores are better, and the contestent with the highest score wins.

As a judge for how sorted a list is, this is basically as bad as you can get. Sequences that a viewer would intuit as “mostly sorted” will regularly score 0, and horribly sorted list will occasionally win points by pure chance. Let’s look at an example:

Sort the Harry Potter novels by release date:

True Order Person A Person B HP 1 HP 7 ❌ HP 7 ❌ HP 2 HP 1 ❌ HP 6 ❌ HP 3 HP 2 ❌ HP 5 ❌ HP 4 HP 3 ❌ HP 4 ✅ HP 5 HP 4 ❌ HP 3 ❌ HP 6 HP 5 ❌ HP 2 ❌ HP 7 HP 6 ❌ HP 1 ❌

Person A has almost all of the list in the correct order, but accidentally put the final novel at the front. Person B has it all wrong though - the list is fully reversed! You might think that Person A should win, but since none of their answers lined up with the correct ordering, they receive 0 points, while person B will get 1 point because the fourth element happened to end up aligned with the right answer.

This is an injustice, and I’m going to get in the comments to fix it.

Defining “mostly sorted”

It’s surprisingly hard to come up with a good way to quantify how sorted a list is, but I think that a good metric will measure how close a candidate list is to the properly sorted version, and the best way to do that is measure how many modifications to the candidate are needed in order to fully sort it.

I think that this approach is intuitive. If I gave you a hand of playing cards and asked you to sort them, you’d probably look through it and then start pulling cards out and putting them in the place where they should go. If the hand was already mostly sorted, it would require only a few changes, but if the hand was randomized, then you’d be doing a lot of re-organizing.

In pseudo-code:

def how_badly_sorted(list):

steps = 0

while not is_sorted(list):

item = remove_an_item(list)

put_it_back_somewhere_else(list, item)

steps += 1

return steps

The trouble with this algorithm is that remove_an_item and put_it_back_somewhere_else

somehow need to know which item to remove and where to put it back in order

to minimize the number of steps that it takes to run. This is a problem for me

as the algorithm developer, but it’s also a problem for a game show host!

Computing the minimal amount of operations that will transform one list into

another isn’t something that you can pause the action to do… so I’m going to

disqualify it, but use it as a baseline to judge the other heuristics against.

For what it’s worth, I’ve implemented a fast-enough version of this using A* pathfinding, but maybe there’s a more clever version - if you come up with one, send me an email!

(non) option 1: score by exact placement

“Score by exact placement” is the ranking system currently in use by Umm Actually. For each element in the candidate list, you receive a point if the index of that item matches the index of that item in the sorted list.

The code for this implementation (and all future implementations) operates on a list of non-duplicate inegers whose value ranges from

0(inclusive) tolen(exclusive). This means that each element in the list is a number whose value is the idex that it should be in the sorted list, which simplifies the implementations of these algorithms a lot!

pub fn score_by_exact_placement(

l: impl Iterator<Item = i32>,

) -> usize {

l.enumerate().filter(|&(i, v)| i as i32 != v).count()

}As we saw in the Harry Potter example earlier, this method fails catastrophically when a list is “almost right” but has one element out of place that throws everything else off. Person A’s answer was objectively better than Person B’s, but scored worse because of this flaw.

Option 2: score by distance

Instead of just checking if each element is in the exact right spot, we could measure how far each element is from where it should be. This way, if HP 7 is in position 0 when it should be in position 6, we count that as a distance of 6 rather than just a binary “wrong.”

pub fn score_by_distance(

l: impl Iterator<Item = i32>,

) -> usize {

l.enumerate()

.map(|(i, v)| (i as i32 - v).unsigned_abs() as usize)

.sum()

}This is already much better! Person A’s answer would score 21 (since every element is off by 1, and we have 7 elements, but the first one is off by 6), while Person B’s reversed list would score much higher. This metric properly rewards partial correctness.

Option 3: score by correct neighbors

This approach counts how many adjacent pairs aren’t consecutive in the sorted list. Even if two elements are in the right order relative to each other, if they’re not actually neighbors in the sorted sequence, it counts against you.

pub fn score_by_correct_neighbors(l: &[i32]) -> usize {

l.windows(2).filter(|pair| pair[1] - 1 != pair[0]).count()

}This is even more strict than the previous metric. For Person A’s list, HP 1 through HP 6 are all consecutive, so we’d only penalize the HP 7 at the front (1 incorrect neighbor pair). Person B’s reversed list would have every pair incorrect (6 penalties).

Option 4: score by runs

Another intuitive approach: count how many “ascending runs” exist in the list. A perfectly sorted list has exactly one run (the whole thing is ascending), while a heavily shuffled list breaks into many separate runs.

For example, [1, 2, 3, 5, 4, 6, 7] has 3 runs: [1, 2, 3], then [5] (which

breaks because 4 < 5), then [4, 6, 7].

pub fn score_by_runs(l: &[i32]) -> usize {

l.windows(2).filter(|pair| pair[1] < pair[0]).count()

}For Person A’s list [7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], we have 2 runs: [7] and

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], so the score is 1 (one break). For Person B’s reversed

list [7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1], every adjacent pair is descending, giving us 7

runs and a score of 6. Person A wins again!

Option 5: score by minimum modifications (the gold standard)

This is what I consider the “true” measure of sortedness: how many moves would it actually take to fix the list? This is the most intuitive metric - it directly answers “how much work is needed to sort this?”

The challenge is that computing this optimally is expensive. You can’t just greedily move elements around; you need to find the optimal sequence of moves. I’ve implemented this using A* pathfinding with the Longest Increasing Subsequence (LIS) as a heuristic.

The insight behind the LIS heuristic is clever: elements that are part of the longest increasing subsequence don’t need to move at all! They’re already in the right relative order. Everything else needs to be moved. This makes the formula simple:

pub fn score_by_lis(l: &[i32]) -> usize {

l.len() - longest_increasing_subsequence_length(l)

}For Person A’s list [7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], the LIS is [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

with length 6, so the score is 7 - 6 = 1 - just one move needed! For Person

B’s reversed list [7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1], the LIS has length 1 (any single

element), so the score is 7 - 1 = 6 moves needed.

This perfectly captures our intuition: Person A’s answer needs just one fix, while Person B’s needs six.

Comparing the Heuristics

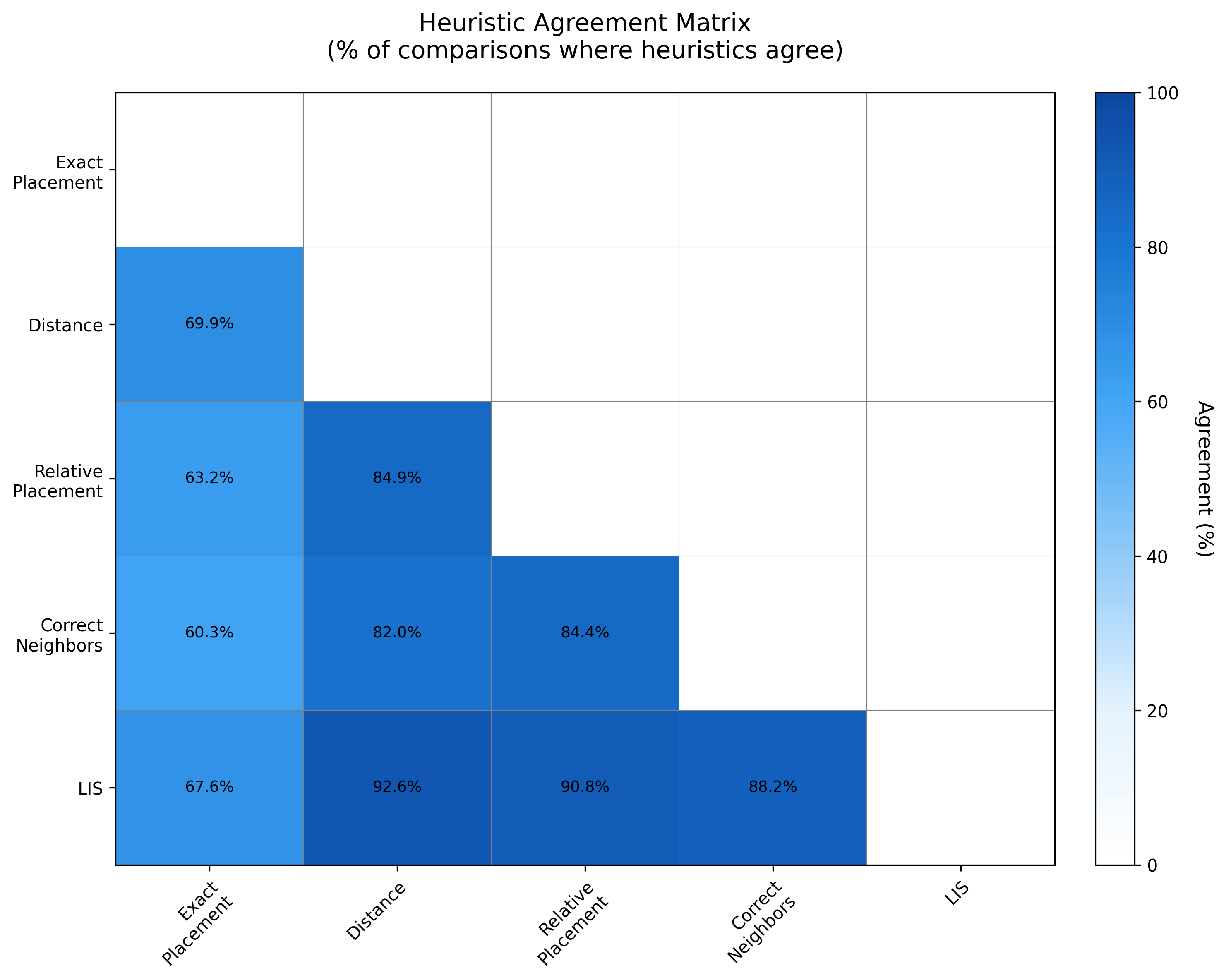

To validate these heuristics, I generated 100,000 pairs of random sequences and measured how often each heuristic agrees with the others. The results are striking:

This heatmap shows the percentage of time each pair of heuristics agrees on which sequence is “more sorted”. The key findings:

- Distance, Correct Neighbors, Runs, and LIS all show very high agreement with each other (typically 85-95%), suggesting they’re measuring fundamentally similar properties

- Exact Placement shows much lower agreement with every other heuristic (around 60-70%), confirming it’s measuring something fundamentally different

- The LIS-based approach agrees most strongly with the other reasonable heuristics while being the most theoretically sound

Conclusion

The “score by exact placement” method used by Um Actually is fundamentally broken. It treats lists as having no internal structure and ignores the notion of “closeness” to the correct answer. Any of the alternatives presented here would be fairer:

- Score by distance: Simple and intuitive, rewards partial correctness

- Score by correct neighbors: Checks if adjacent elements belong together

- Score by runs: Counts ascending subsequences, easy to visualize

- Score by minimum modifications: The most accurate, measures actual work needed

My recommendation? Use the LIS-based approach. It’s computationally efficient, easy to explain (“count how many items you’d need to move”), and it matches human intuition about what “mostly sorted” means.

Until Um Actually fixes their scoring system, I’ll be sitting here, arms crossed, ready to say: “Um, actually… your scoring algorithm is broken.”